The field of software engineering is in a strange place today. A lot of the mainstream tools and concepts look less like deliberate choices made by intelligent people anticipating change and more like ad-hoc reuse of things some people were already familiar with, despite the problems this may cause at scale. Things I consider to be concrete examples of this are all the major programming languages (Java, C#, Python, C++ that don’t even have algebraic data types that are around since the 70ies), docker containers (where the usual way of constructing them leads to linear dependencies which lead to poor composability), YAML as a configuration format (with its many pitfalls and high complexity), Microservices as almost a default architecture choice - the list goes on. This is not to say that I don’t consider these things useful in certain situations - it just strikes me as odd that the majority of our industry sees little problem with the status quo of defaulting to these options and that there are so few attempt at improving things.

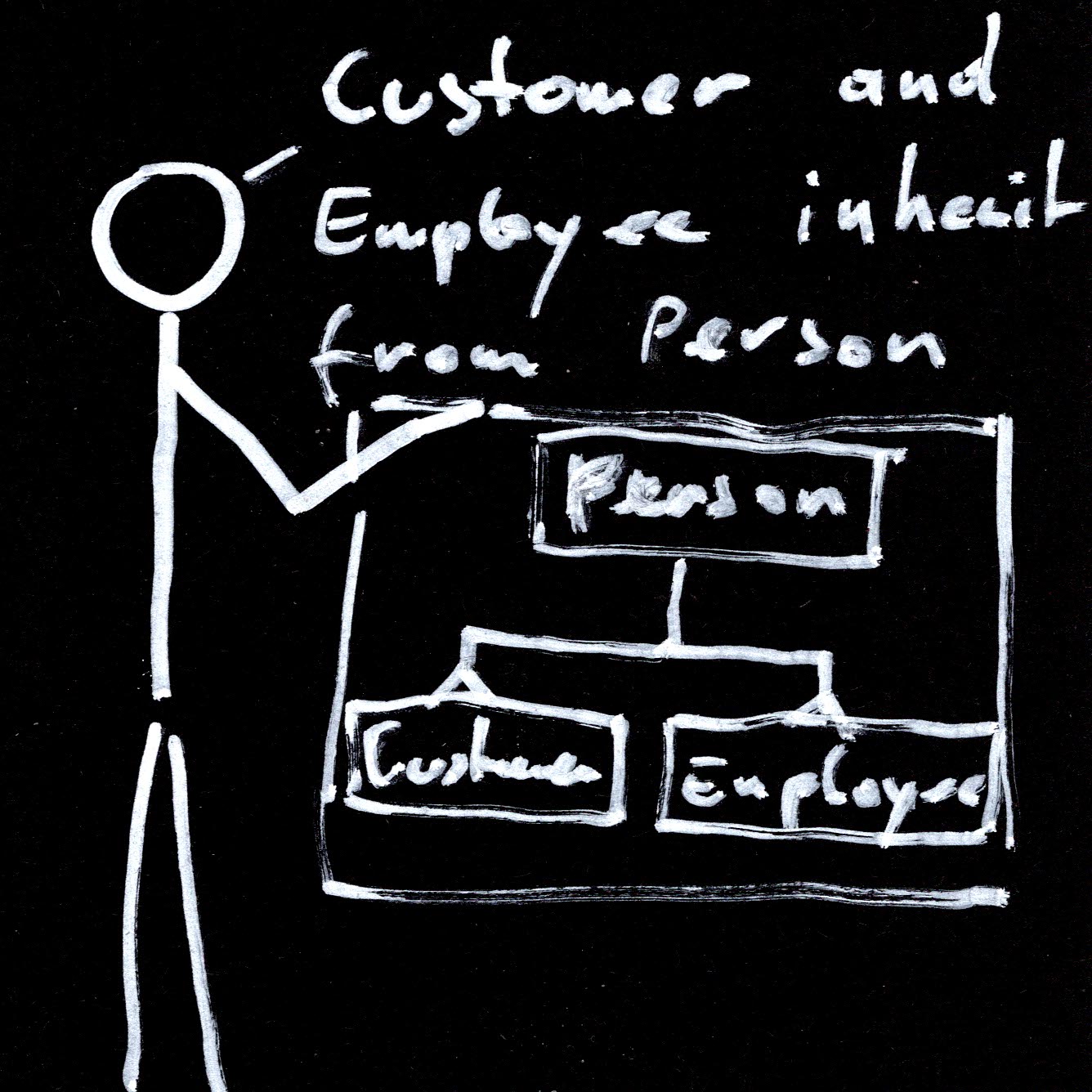

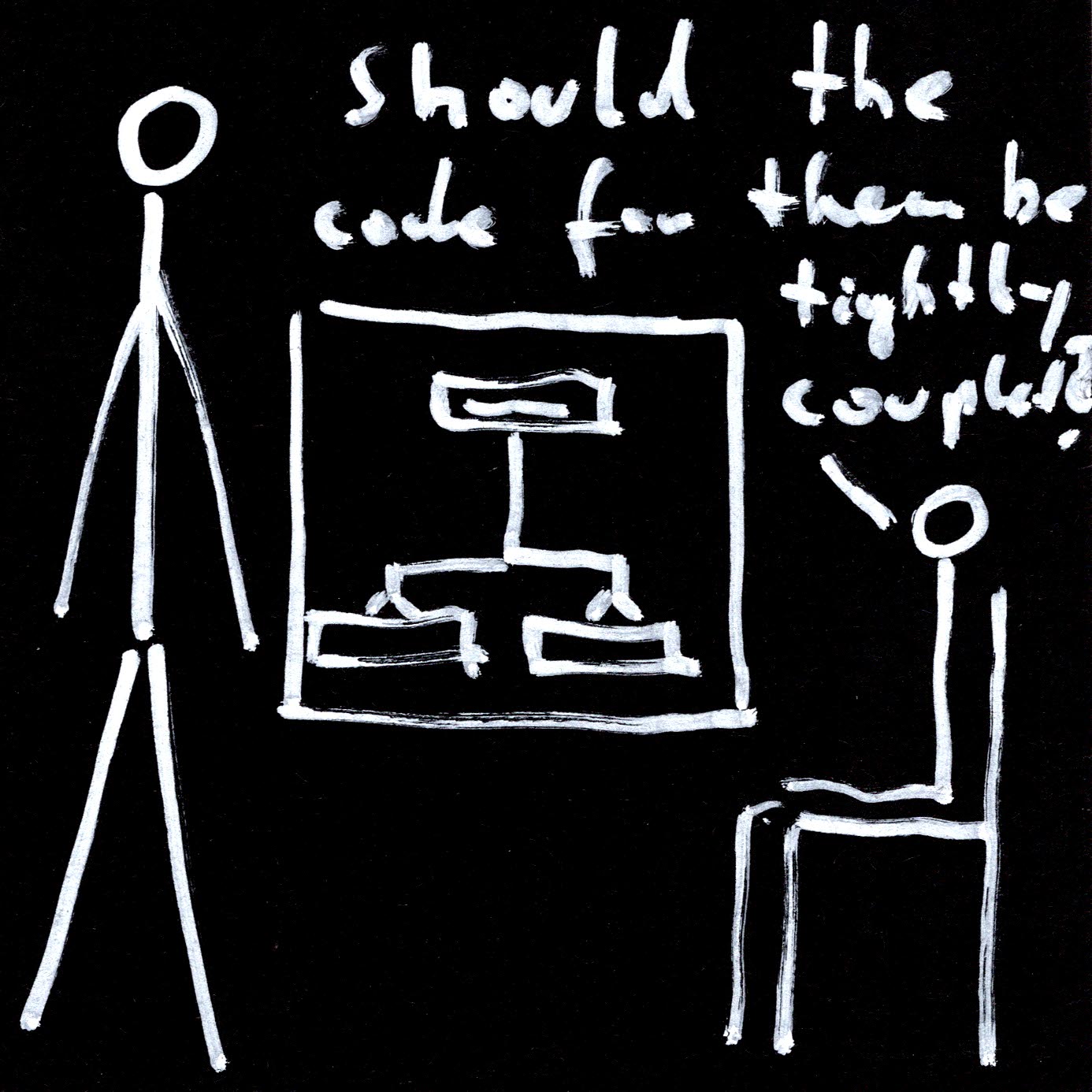

Maybe my experiences with Elm and F# have spoiled me - I was lucky enough to use both on my job for the last three years. I feel like so many of the problems I regularly encountered in the previous ten years of doing mostly C#, some Ruby, Python, Javascript and C++ - are just gone. In Elm (and with some caveats in F#) you don’t need to worry about null values or exceptions; you don’t spend your time discussing pointless ontological questions and creating strange inheritance hierarchies that couple logic depending solely on the answer to the question “Can you say A IS-A B?”.

|

|

|

In Elm, F# and similar languages, you write functions that deal with data, you model data in different forms accurately with algebraic data types and you let the compiler use the types to check if the shape of your data matches in all places. Because values are immutable, state changes only in a few well defined places. Elaborate “magic” like two-way databinding is replaced with simpler patterns like the Elm architecture. Such patterns look a bit more verbose in the beginning, but as the application that uses it grows it always behaves predictably. This is something I have never seen with two-way data binding UI frameworks at non-trivial scale.

Of course types are not everything and using Elm or Haskell etc. to implement some software will not magically make it bug free. But what they afford you to do is to concentrate on the interesting parts of your code and test more interesting properties since the technicalities are taken care of by a compiler. Refactoring complex pieces of software becomes a mundane tasks of following compiler errors instead of the Russian roulette it is in languages without static typing or with a poor type system. Since software tends to grow in size and requirements tend to change, I consider this to be a big advantage.

All that is not so say that languages like Elm, F#, Haskell and Purescript cannot improve further. By listening to the excellent Future of coding podcast I found Pharo, a language strongly inspired by Smalltalk, and the Glamorous toolkit. The Glamorous toolkit places a high value on an interactive canvas that can be used to understand your code. How great would it be if there were a standard way for an ML family language to ship interactive debugging UIs with standard libraries that aid in your debugging and REPL experience? Think e.g. a monadic probability library that visualizes distributions while you work with it in the REPL.

The power of Erlangs VM with hot code swapping and supervision trees is very desirable, even more so if messages could be typed with something like session types. Algebraic effects like in the Eff language look like a very promising way for handling side effects (I/O, concurrency, exceptions, …), so they can be separated from the pure code but without the pain of monad transformer stacks. Datomic which is built in Clojure is a really interesting way of dealing with data queries and between that and Prolog I think there is a lot of unexplored scope of embedding reasoning/analytics engines in ML family languages.

I find it strange that not more programmers see the value of ML like languages for larger projects. Do so few know these languages in enough detail? Is the inertia so powerful, the desire to stay with what you already know? Many of the excuses of a few years ago, like bad editor tooling or small ecosystems apply less and less (and some languages have a strong FFI that lets you tap into other languages’ ecosystems).

Maybe one of the reasons is that evaluating technologies is often done on small examples where ease of setup and the speed of getting started are most important. Problems that only arise in bigger projects show up too late and by this time get confused as “this is just what programming in a large project looks like”.

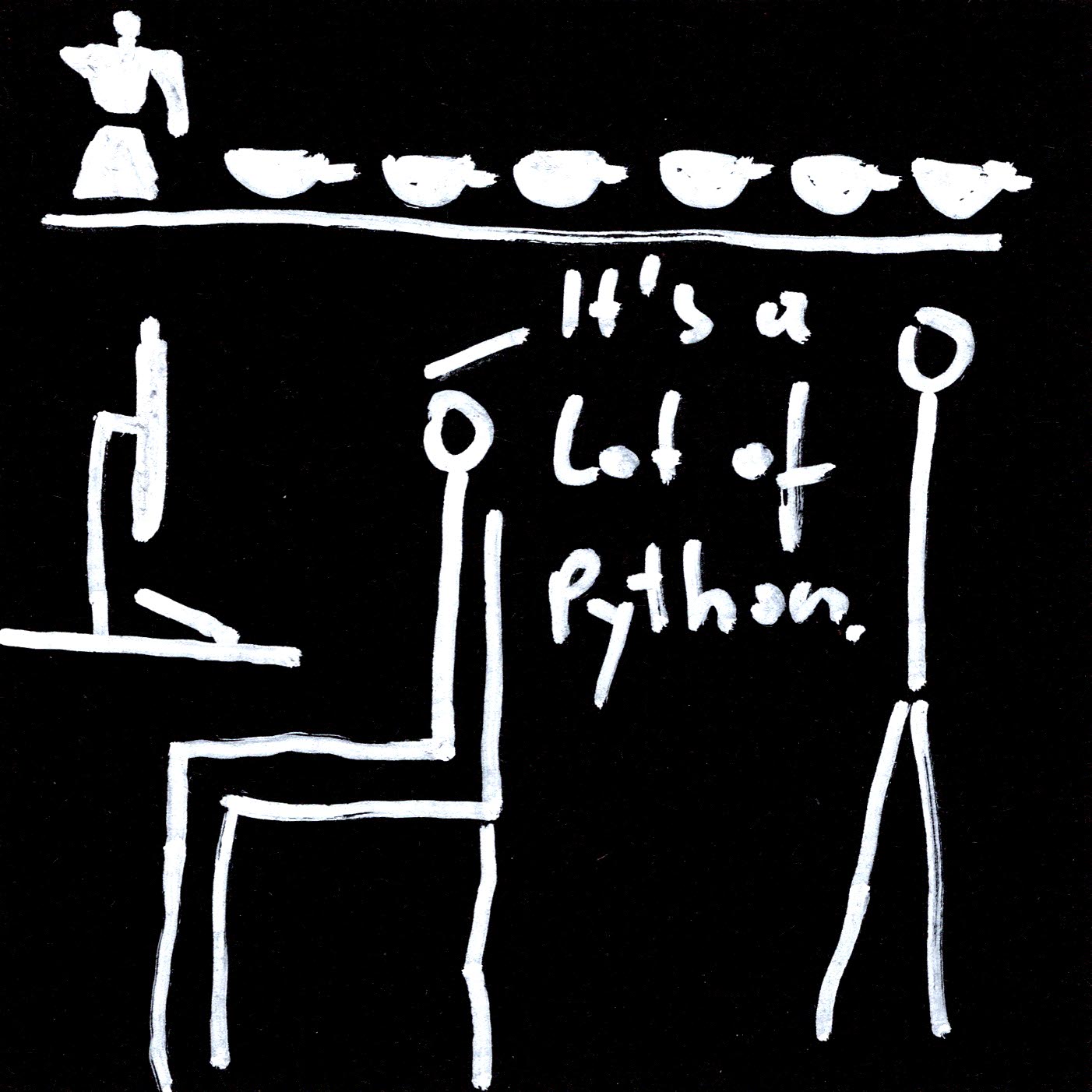

At my job we have one relatively complex backend written in Python - because at the time GraphQL support in ML languages was not developed far enough. To give praise where it is due, the Django admin interface was also a huge time saver - oh how I would love something like it to exist in F# for the SAFE stack! We were very fast initially in getting the first version out but now every non-trivial change is a pain and we are just so slow in that codebase compared to the F# backends (and we make more mistakes). If I hadn’t had the F# experience, I might’ve mistaken this slowing down for an inevitable fact of refactoring code.

|

|

Maybe none of this is so surprising given how young our field is. The first people who worked with textual instructions for computers did so from around 1950 - if you assume that the working lifetime of a person is around 40 years then this is not even two generations ago. In that time we scaled from a few hundred to maybe around 20 million programmers. Pretty much all other engineering professions or crafts developed over much longer timespans and with an only moderate change in the number of practitioners from decade to decade. They had time to try ideas and evaluate their outcome over long timespans and to develop cultural institutions like guilds or engineering societies. To complicate matters, computers kept getting faster at an insane pace for most of the last 70 years - so received wisdom from a generation ago is often no longer applicable. Maybe these are just growing pains of a still relatively new field then?

I would be more relaxed about this if it were not for the fact that the stakes are getting higher all the time. We are putting software into ever more areas of human life and into ever more critical situations - but the tools that are mainstream in our profession are error prone and limit our expressivity. Software development is still so often at the same time intellectually challenging and incredibly boring even in the best of cases.

Some things give me hope, e.g. Rust is a great new language that improves many things for system programming from the previous status quo - and it seems to gain traction lately (Microsoft Security recommended it recently).

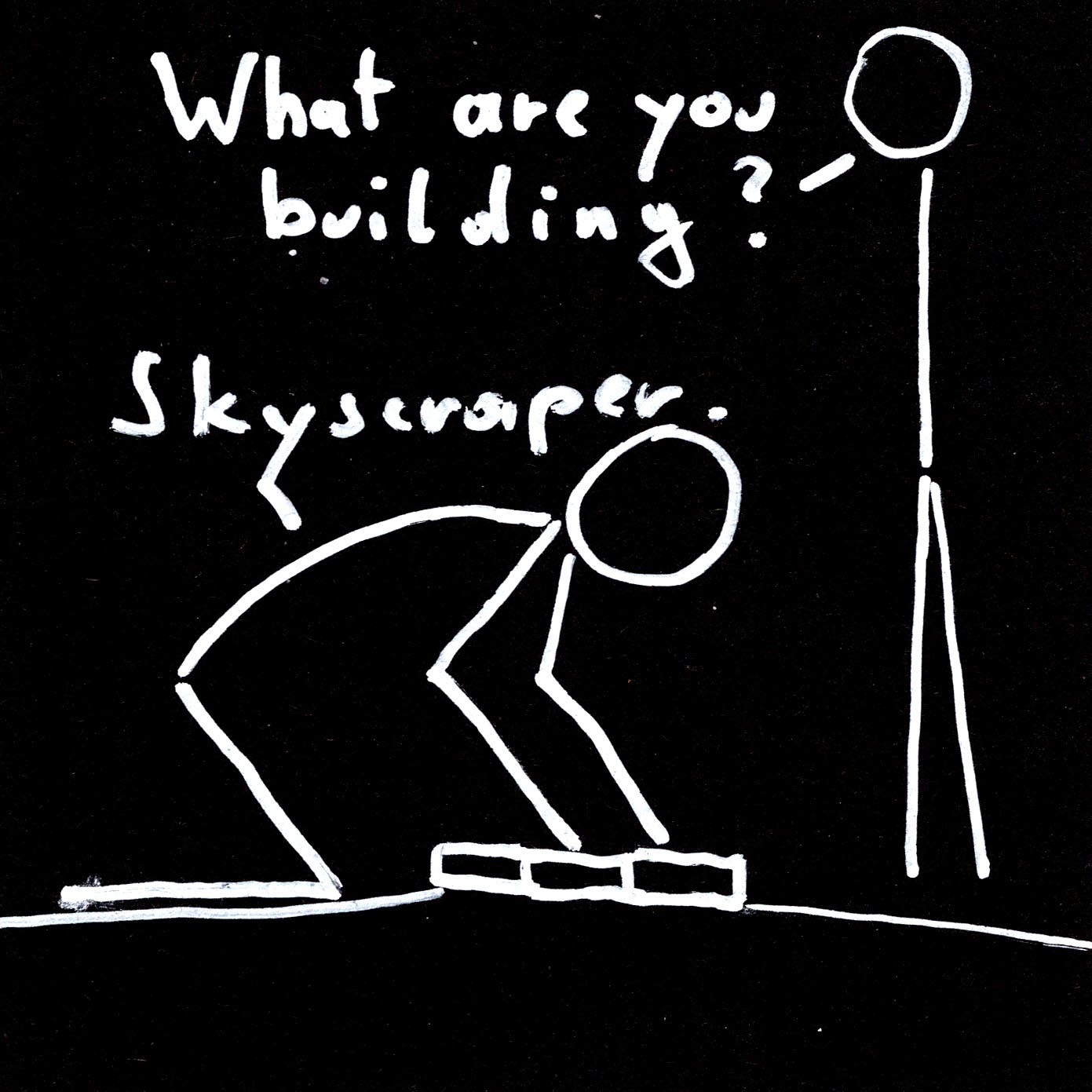

But when it comes to mainstream adoption, we are still so far behind what is easily possible today. So much software is buggy and needs crazy amounts of development time and is just so brittle all around. Metaphors are always problematic, but it feels a bit like as an industry we insist on building skyscrapers with clay and neglect to learn how to work with steel and concrete for no good reason.

|

|

|

I try to spread the word about these ideas with things like the Friendly Functional Programming Meetup Berlin that I run together with Michael, but I often feel like such events mostly reach those that already see the value of functional programming. I think our best bet is to work on creating entire toolchains that work well for pragmatic applications and then showcasing those. I think Elm did a good job on the web frontend side; the SAFE stack does so quite well on the backend as well as the frontend; and Servant does a great job at showing how useful full type level representations of HTTP APIs are because they let you type check both the client and server of a REST API at compile time from the same type definitions.

I think as enthusiasts of these languages we should talk more about the pragmatic ways these powerful tools can enable us to do more work in less time to a higher quality standard. We should try less to explain Kleisli composition to outsiders (not that this is not useful, but the focus should be on the former IMHO). Maybe then we will find ourselves in a future where software is built on top of good abstractions, at high speed, and can be safely changed and modified. Let’s work towards that future.