In the last few months, climate change has been discussed with renewed vigor in the media and on social networks. More and more people realize that we have a problem but a lot of the current focus doesn’t seem to be directed at the pragmatic goal we should be aiming for: mitigating climate change as far as possible.

Increased levels of greenhouse gases in our atmosphere are the cause of climate change, and so the metric we need to look at is our global net total greenhouse gas emissions going forward (i.e. the absolute amount of CO2 or other greenhouse gases emitted minus whatever we manage to extract out of the atmosphere through additional trees or via technological means). Reducing our emissions quickly to a low enough level will be a tremendous challenge.

I wrote this post out of frustration with the current public discourse that doesn’t focus on achieving this goal effectively. I am not a climate scientist and thus this post can only collect a few high level ideas that I consider important but neglected. I tried to collect some numbers that provide a useful frame of reference, but of course they cannot give a complete picture. Take what I write with a healthy dose of skepticism - but I do hope that it will be valuable perspective.

The current discourse

A lot of the current public discussion focuses on personal consumption lifestyle choices and moral arguments and I think that this is a harmful distraction. As Elizabeth Warren recently said in her poignant style:

“This is exactly what the fossil fuel industry wants us to talk about. … They want to be able to stir up a lot of controversy around your lightbulbs, around your straws, and around your cheeseburgers, when 70 percent of the pollution, of the carbon that we’re throwing into the air, comes from three industries […] construction, electricity generation and the oil industry” – Elizabeth Warren

I see three main problems with the personal consumption and lifestyle choices arguments. First, it seems to me that public attention is a very precious good and that one can think of this as a public attention budget that is quite limited. Concentrate too much on actions that have only very minor impact on absolute CO2 emissions and you risk saturating your audience without having much effect. It is therefore important that public attention is focused on getting the big political solutions in place and not waste time debating whether or not eating beef is morally justifiable.

Second, framing the problem as a moral question of personal consumption choices just does not have enough potential to reduce absolute emissions by a significant margin. Aviation for example accounts for 2% of global emissions. A voluntary consumption cut by rich consumers will not change nearly enough and we have to instead focus on aligning the entire global economy to emit less, going to net zero at some point this century.

Third, the current rhetoric of moral arguments often invokes images of catastrophe. Tackling climate change is framed as a binary choice between dramatically changing everything — or extinction. In this lies a real danger of evoking hopelessness: the whole world will not change dramatically all at once, so why bother doing anything at all, especially giving up things you personally enjoy? If the situation is hopeless, shouldn’t we just enjoy it while it lasts?

A different focus

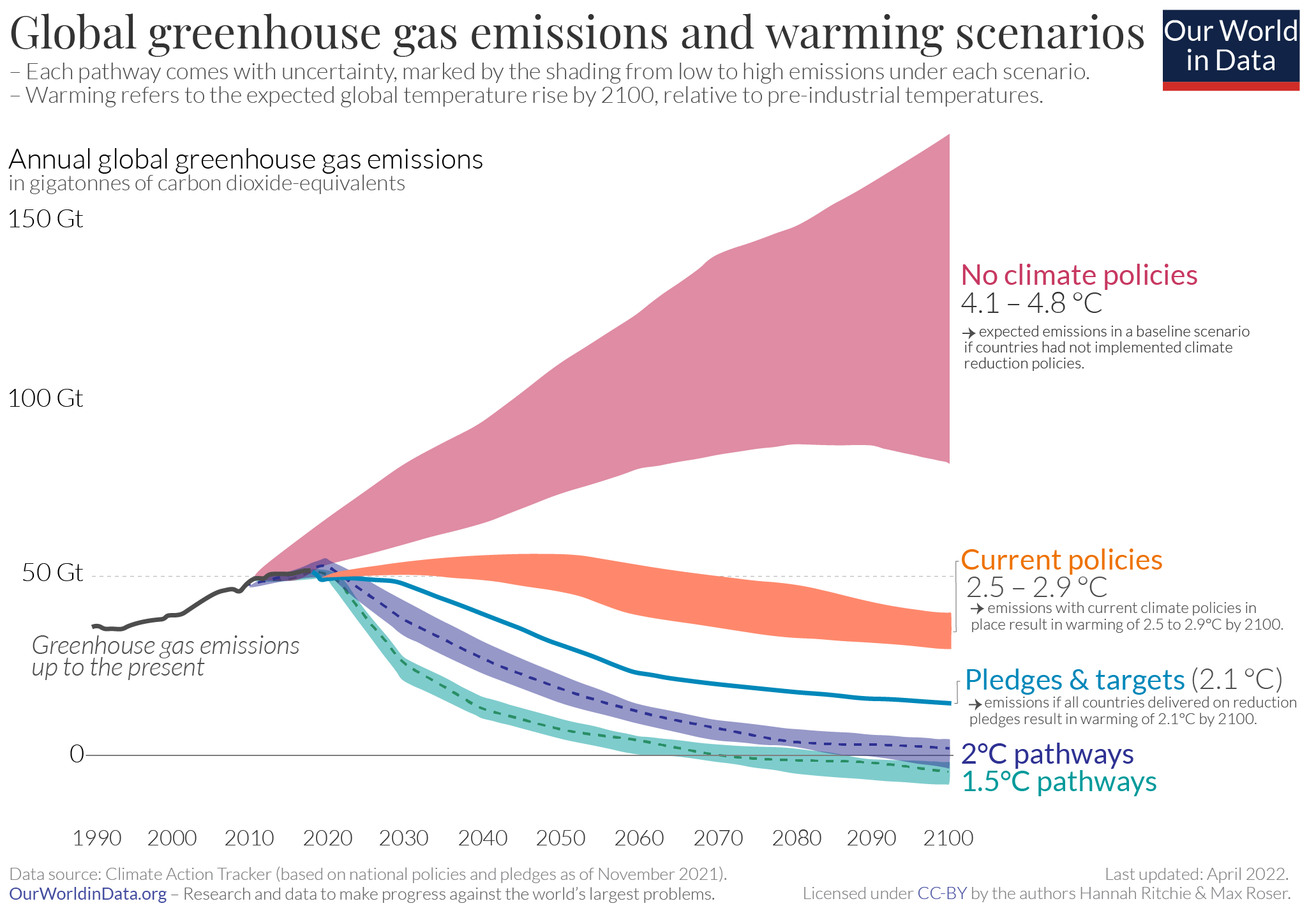

Instead we should aim for solutions that can bring down absolute greenhouse gas emissions effectively and focus minds first on the areas that can really make a big difference. As I will outline below, I doubt that we will be able to still achieve a great or good outcome (staying below or 1.5 degrees or 2 degrees Celsius global warming respectively). Timeline to reach certain temperature thresholds given the emission trajectory. We will pass 1.5 degree Celsius around 2030 in pretty much any scenario - figure by The Economist

But if we can focus on areas where we can make big gains for moderate cost then I think it is still very much possible to achieve a moderately bad outcome of somewhat above 2 degree Celsius versus extremely negative outcomes for ecosystems and human livelihoods if we end up at 4 degree Celsius or above as is our current trajectory.

If the reduction of absolute greenhouse gases is our goal, I think we should focus public discussion on the following three main areas:

- a steadily increasing emission tax or carbon tax to align profit incentives with emission reductions goals and let the market help with figuring out which emissions are the cheapest to replace first.

- more research, development and bootstrapping of technologies to reduce emissions — especially in the neglected agricultural and steel/cement producing sectors as well as electricity storage

- a creative diplomatic effort to create strong (trade) incentives for the big emerging economies to refrain from deploying coal for electricity production

An outline of the problem

To frame the discussion, I think it is useful to recall a few important numbers. The scientific opinion of the UN’s panel for climate research, the IPCC, is that we should try to constraint global temperature rise by 2100 to ideally 1.5 or at most 2 degree Celsius versus pre-industrial average global temperature.

A greenhouse gas emission budget can be calculated which expresses how many Gigatons of CO2 equivalent we can still put into the atmosphere to stay within a given temperature target. For 1.5 degrees, we have about 400 Gigatons left Estimates for the budget to stay below a certain temperature target vary quite a bit but most are in this ballpark; this one is from the German MCC institute; Wikipedia has a good overview of other estimates . We currently emit around 45 Gigatons CO2 equivalent per year (around 35 Gigatons CO2 as well as Methane from agriculture that is equivalent to another roughly 10 Gigatons of CO2 in its immediate effect).

Trajectories for attempting to stay within a 600 Gigaton CO2 budget - figure by Stefan Rahmstorf via Wikipedia If you do the math, this means we can go on emitting at the current level for around 9 years and then have to go to 0 net emissions immediately; hardly a realistic scenario. A smooth curve that reduces emissions steadily would still have to reduce emissions year on a year on an unprecedented level for all countries and all sectors simultaneously. Whichever way you turn it, the 1.5 degree target looks pretty unrealistic at this point.

To stay within 2 degrees warming, we have about another 800 Gigatons left. This gives us another 18 years or so at current emission to be distributed over the next few decades. Unfortunately, the trend curve of global emissions does not point down — it is instead still rising:

There are stark differences in our capacity to replace certain kinds of carbon intense energy sources. Some, like using kerosene for aviation will be very tough to replace because of the incredible energy density of kerosene and similar fuels. But in other areas we are much closer to fully replace them. The most significant such example is using coal for the generation of electricity and heat. Using coal for electricity and heat production makes up around 40% (!) of all CO2 emissions. In addition to that, burning coal pollutes the air, not just with harmful soot, dust particles and smog but also with substantial amounts of radioactive isotopes. Yet for electricity generation we now have tools like wind and solar power that are cost competitive with coal (and in many parts of the rich world already even cheaper). Full replacement is not yet possible with current technology because we are missing the crucial ingredient of durable large scale energy storage, but we could already replace a large fraction of coal power plants today with renewables given the will and the right economic incentives.

It is worth noting that the higher the temperature increase will end up being, the worse the repercussions for our ecosystems and our habitable areas and global living standards will be. Thus, even if we slightly miss the 2 degree target, this would be a much better outcome than the ~3.5-4 degree increase we are currently on a trajectory towards. This article by Glen Peters, a climate scientist at the Cicero institute for climate research in Oslo is a sobering look at the feasibility of staying below 2 degrees

If we look at emissions by region we see that absolute emissions have started to slowly decline in the last few years in both Europe and the US, although at a very slow pace. At the same time, the emissions of especially China rose very quickly as it become wealthier and had big construction and energy needs. Climate diplomacy should therefore be an important part of the solution, but let’s first look at the things that rich countries (such as Germany, where I live) can do by themselves.

The case for a carbon tax

Quite a few climate activists on the left argue that Capitalism is to blame for climate change and that to combat climate change we should reach for non market based solutions; consumption overall should be lowered, either voluntarily or, if necessary and possible, by force. I think that this is wrong and that we should instead try to come up with incentives and mechanisms that align capitalist interests with reducing emissions. GDP growth is not intrinsically linked to growing resource consumption as the service sector can be a driver of GDP growth. Emissions and GDP growth are already decoupling in rich economies with emissions slowly falling and GDP steadily increasing — we now have to speed this process up. One great way of doing this is a carbon tax that would be levied on all forms of fossil fuels. At a sufficient level it would bring corporations and people to reduce their emissions just so they pay less in taxes. It would mean that areas where switching to clean sources of energy are easiest and therefore most lucrative would do so first, out of pure monetary considerations.

An emissions trading scheme if designed well could also work instead of a carbon tax; here, a fixed number of certificates for emissions is generated by the state and these are then traded in a market where polluters have to buy certificates for their emissions. The end result of both strategies when designed well is similar, just the way of getting there is different. In a trading scheme the emissions are fixed and the price is cleared by the market; when using a carbon tax, the price for emissions is set and the emissions fall accordingly. I slightly prefer a carbon tax because the stable and increasing price can be used for long term planning. It is also more transparent: the price for heating oil for the normal consumer would carry the same markup as that paid for industry that burns coal for steel production per unit of CO2 emissions. But both would be fine if the details are right.

Even an imperfect tax would already be a good step. Three things are important to get right: first, a carbon tax has to include all sources of energy that come from fossil fuels, including coal used for electricity production. Second, the tax has to start at a high enough level (35-70 Euro / ton of CO2 is thought to be an acceptable level and is also what international oil companies anticipated and used for the past few years internally to decide long term investments Estimates for the social cost of a ton of CO2 vary substantially. The 35 to 70 EUR / ton of CO2 is referenced here e.g.. Vox has a good overview of carbon tax proposals that talks about various issues of carbon taxes ). Third, it should subsequently increase year by year by at least a few percentage points (a 3% annual would mean a doubling of the tax every 25 years, a more ambitous 7% annual rise would double the price every 10 years) to constantly raise the pressure on emitters.

One of the most important effects of a carbon tax (at a high enough level) is that it would make running existing coal power plants uneconomic in the near future in the rich world. By making emissions from firing coal more expensive, the markets would have an incentive to switch to lower emission alternatives.

Looking at the transport sector, modern cars emit a ton of CO2 for roughly every 8.000 kilometers they drive The EU mandates that new cars can only emit a certain amount of CO2 per driven kilometer. It targets fleet wide averages, the current of 130g CO2 / km is from 2015, for 2021 a lowering to 95 g CO2 / km is planned . Coincidentally, the amount of CO2 emitted when travelling by airplane in modern passengers airplanes at close to capacity is roughly similar for the distance travelled - traveling 1000 km via plane produces roughly the same emissions as travelling the same distance alone in a car Carbonindependent has an overview that shows how this comparison is calculated. Raw CO2 Emissions are actually lower per passenger kilometer at around 90g CO2/km but emitting them at high altitude is probably significantly worse for the climate and so the number that is used is 180g CO2/km, somewhat higher than that of cars. It shows how crazy inefficient our cars are with their heavy weight and poor energy efficiency. . Kerosene, the fuel for jets, is not taxed at all for international flights, which definitely has to be rectified. If you were to apply a carbon tax to Kerosene as well at initially 50 € / ton, a plane ticket for a return flight of a distance of 1000 km would incur additional initial taxes of around 15 Euros.

In transport one interesting thing is that taxation is so different in different areas for historic reasons. Petrol and diesel for cars is taxed quite substantially already in many European countries, in Germany for example at 65 cents / liter for petrol which comes down to around 250 € / ton of CO2 I have created a Nextjournal notebook with this and various other auxiliary calculations . The revenue of the tax is in parts used to pay for roads etc. but in the context of a carbon tax it can already be seen as increasing the wholesale price by a government decreed level.

In Europe the goal should thus be to create a carbon tax that acts as a minimum base line of taxation for all uses of fossil fuels (especially coal and kerosene), while leaving the higher petrol prices where they are at the moment but maybe shifting how the revenues are used (see below).

In the US to the best of my knowledge the current level of taxation is far too low (and there are even tax breaks for certain forms of fossil fuels). In the US as well as in other rich countries where fossil fuels aren’t taxed at this minimum level, introducing a carbon tax should be a main political goal.

To make such a tax politically viable and avoid broad opposition, the windfall from such a tax should be directly sent to citizens as quarterly or yearly flat per capita cash payments (as opposed to lowering income taxes or similar which would be less visible and would benefit richer people more). This way companies and individuals could each try to lower their particular fossil fuel consumption to pay less tax and the proceeds would be distributed equally, thus being very regressive in effect since a few hundred euro a year are a much bigger benefit for a poor family than for a rich one.

If a carbon tax would be levied at 50 € / ton, the tax income for a country like the US given its current emissions would be around 240 billion €, so every resident would be paid around 750 € per year This and other calculations in this post can be found in this Nextjournal notebook . Inequality is a big concern when it comes to energy taxes since often rural populations are both poorer and have higher energy consumption needs per capita. However, since the tax would be collected from industry as well as individuals but the proceeds be paid out to individuals only, the immediate additional expenses from fuel and heating should be offset by the payouts for most people, including poorer rural families (indirectly the costs for energy intensive products would rise by the additional taxes incurred in their production but I think that such effects would not be as visible to consumers and consumed more by higher income segments)

Vested interests in energy intensive export industry will rally against this on the grounds that it will disadvantage them versus their international competitors. Here I would argue that this is not a strong enough reason against such a tax given the overall benefits. Additionally, by pioneering low carbon technologies they will be in a much better position internationally in the medium term when other countries follow suit. But in the end it will be a political fight to get companies to accept this.

Research and technology

The second area I think we should focus on is investment in research and development of climate change mitigation technology. Rich countries should lead the way here and heavily invest in such research and share the proceeds generously with poorer countries. We need to think about different time horizons and find solutions to help over the short term (the next ten years), the medium term (the next 25 years) and the longer term (technology that will only be ready in the second half of the century). We should raise budgets for research and development drastically — the earlier we get new technology to a point where it can be used, the more impact it will have over the course of the 21st century. We need innovation in many sectors, but here are a few promising areas and ideas:

For the short term, one area of research and development to focus on are sectors with big emissions that have been neglected so far, like agriculture and construction. To get an idea of the magnitudes, consider that if we could half the emissions of producing concrete we would do much more for the planet than if we got rid of all air traffic (aviation accounts for roughly 2% of global emissions, cement use for 8% Chatham house is a good resource on lowering cement emissions. Gatesnotes has a great broader overview of ideas around construction that incorporates plastic and steel ). Among the promising research ideas for agriculture is the idea that adding a little bit of certain algae to the feed of cattle drastically reduces their Methane emissions MIT Technology review has a good article about this .

Electricity production is responsible for a large part of CO2 emissions because a lot of it is produced by burning coal, oil or gas. Luckily with photovoltaics and wind power we already have cost competitive alternatives, but the big missing part is electricity storage on a grid scale. Chemical batteries are expensive, toxic and have limited live times. The main tool we have to store electrical power is water pump storage, where excess electricity is used to pump water up into the dams of hydro power stations and then released again when demand is high. Innovations will be desperately needed in this area and should be a big focus of research. One interesting approach for electricity storage is the idea of stacking concrete blocks on top of each other to use them similar to pump storage, like Energy Vault is planning to do See the Energy Vault website for an animation of how this could work. If this could be scaled up it would make a great combination for large scale solar installations . Synthesis of complex hydrocarbons from atmospheric CO2 with renewable electricity directly from sunlight via artificial photosynthesis would also be a promising avenue of energy storage, since the existing oil based infrastructure we have could be used with such CO2 neutral fuels. All of these areas would be a good examples in the short to mid term category.

Finally for the long term we should start doing research and development for alternative means of “negative emissions”. These are ways to get CO2 out of the atmosphere again - either by using new technology or, more traditionally, by planting new trees. Remarkably, all IPCC scenarios that end up with warming of less than 2 degrees Celsius by 2100 depend on large amounts of negative emissions in the second half of the 21st century - there is simply no realistic alternative anymore for getting there with emission cuts alone.

Planting trees, especially ones that grow quickly like the Empress tree is a remarkably efficient way of getting CO2 out of the atmosphere Bloomberg has a good story about the Empress Tree. These trees use a cellular energy pathway called C4 carbon fixation that is more efficient at extracting carbon from CO2 than that used by most trees (it is common in grasses though) . It’s something that we will probably have to do on a significant scale. But there might be room to create even more efficient ways of capturing carbon out of the atmosphere. One such example is carbon capture and storage, where carbon is extracted at concentrated producers (e.g. industry plants that can’t easily substitute generating CO2) and then stored underground or turned into hard form and used in other ways Ycombinator has a great overview of some approaches in this space . There might also be more efficient ways for biological cells to sequester carbon from the atmosphere. The naturally evolved plants and trees that use chlorophyll reflect green light instead of appearing black which means that they absorb a large fraction of visible light spectrum, probably because they would otherwise get too hot or accumulate too many free radicals. It is possible that bacteria or other small organisms could be optimized for absorbing CO2 from the atmosphere with much higher efficiency.

We should also put more research into a viable plan B for the case where we can’t get enough global cooperation to reduce CO2 levels enough and carbon capture turns out too expensive and we need to try and cool our planet directly with geoengineering. It would be best if we never need to use such solutions, but it would be prudent to start developing them now — just in case.

We should also try to be clever in how we push technologies that are getting to the cusp of viability by designing competitions with big prizes for commercialization (Similar to what the US military arm DARPA did in the early 2010s for self driving vehicles). We should subsidize carbon mitigating technologies that are not competitive yet. Germany half-knowingly did something like this in the 2000s with their subsidy for solar power - it created a solar industry (first in Germany, then in China) which led to the rapid tumbling of prices of production. Because of this we now have solar energy that is so cheap that in many places it is cheaper than coal for new power plants. (But at the same time we of course have German consumers fed up with high prices that make it hard to get off the dirty lignite coal — getting the balance right in theses things is hard).

Climate diplomacy

But neither a wide use of carbon taxes in rich countries nor strong research programs will make much of a difference if we do not also focus on another crucial element: climate diplomacy. Today, China emits more greenhouse gases than the US and Europe combined. Both India and China are rapidly building new coal power plants. As their wealth and living standards improve, many not-yet rich countries will need energy and construction on a large scale (yes, some of the emissions attributed to China are for products that are exported to rich countries but this is only about ~13% of China’s total emissions Our World in Data has more information on this topic ). In absolute terms, coming up with good solutions to reduce these emissions is of paramount importance.

Here I think we should get creative with trade deal incentives and similar offerings. If the EU could strike an attractive deal with China that would hinge on the condition of replacing (or refraining from building) coal power with clean alternatives, then this might be a tremendously effective way of reducing emissions. Additionally, such a deal could provide a blueprint for other countries as well — the greener you build your electricity grid etc, the more we open our markets for you. An example of this could be that “low emission beef” could be exempt from import duties.

A historic blueprint we could use as inspiration is the Marshall plan. Europe, the US and Japan should think about ways of using direct investment and similar tools on a large scale to create clean energy in emerging economies. Another area that is worth thinking about is how to reward countries with forests for not destroying those in favor of short term profits. The challenge will be to create good incentive structures and modes of governance; it must not become a form of eco-colonialism. If we get this right, it could have a huge return investment in terms of greenhouse gas emissions.

In this post I focused on net absolute CO2 emissions but very often you hear different arguments that are based on per-capita emissions or historic total emissions. They can be a backdrop for political solutions but in the end the only thing that matters going forward are absolute emissions. Indeed, rich nations got rich by consuming vast amounts of carbon based energy and still consume more fossil fuels per capita. But high historic emissions in the rich world can’t translate into emerging economies now using similar amounts of fossil fuels. The moral dimension of the argument should translate into a strong research effort and sharing the results freely, thus helping other countries walk a better path towards prosperity while still becoming rich. Add to this that most of the “low-hanging fruit” regarding CO2 emissions will be found in the world’s coal power stations that are active now or currently under construction, many of which in the emerging economies. We all have to reduce our greenhouse gas emissions, but we shouldn’t let per capita arguments get in the way of efficient solutions.

What can we do?

This problem of tackling climate change is very hard — our governance structures and decision horizons are ill aligned with the scale and duration of the problem of climate change. The situation is bad, but we have the power to drastically lessen a potentially terrible outcome for the wider ecosystems, ourselves in the future and for future generations.

So what are we to do as individuals? I think the primary focus should be to push politics and public discourse to concentrate on effective means to reduce total global emissions via any means that work. In the rich countries we should make sure to do our own part and not look hypocrite (looking at you, German lignite plants) — but the best leverage for the overall picture will be to unleash the power of technology and market incentives while making sure that they help the currently growing countries the most.

If you are a politician (or know one), try shifting the position of your party towards effective means of greenhouse gas emission reduction. If you are a journalist (or know one), I think it would be great to use the limited airtime the topic of global warming has to focus minds on the big payoffs, not on small individual contributions. If you are neither, think about where you can influence public discourse in other ways - attending demonstrations, writing about it, or making the case face to face. In all of these efforts, the focus should be efficient reduction of absolute global CO2 emissions and aiming for big wins in all areas where they are possible and to demonstrate that as voters we want a carbon tax and similar measures to be enacted.

If you are in science or technology, consider switching to research or engineering related to global warming, especially in currently under-appreciated areas. So far the only time I would say international coordination in favour of climate policy worked well was around banning CFCs to stop the destruction of the Ozone layer (which also had a huge mitigating effect and avoided even faster global warming). Political action was only viable because technological alternatives were available (and affordable). In many areas today I think we are still missing economically viable alternatives to current greenhouse gas emitting technology. Bret Victor’s essay “What can a technologist do about climate change?” is an excellent resource on framing the climate change problem and thinking about technological solutions.

If you are in diplomacy or a think tank, consider switching to a role where you can come up with creative ideas for climate diplomacy. This is a space that I think is currently woefully neglected to a point where even the European Green parties don’t seem to give it much thought. We need to push this idea into the political mainstream.

Finally, I think it’s important that global warming becomes a major point in making voting decisions — basically a party without a clear agenda to effectively reduce greenhouse gases should stop being a viable option for as many people as possible. It is my hope that this will play out more and more at least in Europe and create competition on this topic between parties. Where currently the various green parties are often seen as the only ones even aiming to do anything in this space there is a big underexplored political space for liberal or center-conservative parties to try to put forward more pragmatic and economically attractive alternatives to the often very ideological party programs of the greens. I would love to see conservative parties giving greens a hard time on global warming topics for mainstream voters — however unrealistic this may seem at the moment.

Working against climate change will be a major challenge for all of us for the rest of our lives. There will be many setbacks and counter trends. But this makes it all the more important to try to target efforts at big absolute reductions that are supported by a large public and not get lost in inconsequential arguments about things that don’t have much potential for bringing absolute emissions down. Let’s work on this. Many thanks to all the people who have read drafts of this post and given their feedback, especially Teresa, Jonathan, Fredrik and Timo.